Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn. Today we’re looking at Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Green Tea,” first published in his In a Glass Darkly collection in 1872. Spoilers ahead.

Summary

Unnamed narrator trained in medicine and surgery but never practiced due to the loss of two fingers. Still fascinated by the art, he became secretary to renowned German physician Martin Hesselius, whose voluminous papers he inherited. Here he translates Hesselius’s notes on a singular case of, what, delusion? Spiritual insight? Read on and decide.

During a tour of England in the early 1800s, Hesselius met the Reverend Mr. Jennings, an agreeable and worthy clergyman by all accounts. Yet he has peculiarities. Though anxious to administer his Warwickshire parish, he’s several times succumbed to a nervous disorder that drives him to London. Hesselius also observes Jennings’s habit of “looking sidelong upon the carpet, as if his eye followed the movements of something there.”

Jennings is interested in Hesselius’s papers on metaphysical medicine, of which Hesselius offers him a copy. Later the doctor speaks to their hostess Lady Mary, for he’s made some conjectures about Jennings he wants to confirm: that the Reverend is unmarried; that he was writing on an abstract topic but has discontinued his work; that he used to drink a lot of green tea; and that one of his parents was wont to see ghosts. Amazed, Lady Mary says he’s right on all points.

Hesselius isn’t surprised when Jennings asks to see him. The doctor goes to Jennings’s townhouse and waits in his lofty, narrow library. A fine set of Swedenborg’s Arcana Celestia attracts his notice. He pages through several volumes that Jennings has bookmarked and annotated. One underlined passage reads, “When man’s interior sight is opened, which is that of his spirit, then there appear the things of another life, which cannot possibly be made visible to the bodily sight.” Per Swedenborg, evil spirits may leave hell to associate with particular humans, but once they realize the human is in the material world, they will seek to destroy him. A long note in Jennings’ hand begins “Deus misereatur mei (May God compassionate me).” Respecting the clergyman’s privacy, Hesselius reads no more, but he doesn’t forget the plea.

Jennings comes in and tells Hesselius he’s in complete agreement with the doctor’s book. He calls Dr. Harley, his former physician, a fool and a “mere materialist.” But he remains shy about the details of his own spiritual illness until several weeks later, when he returns to London after another abortive attempt to minister in Warwickshire. Then he summons Hesselius to his somber house in Richmond and spills his story.

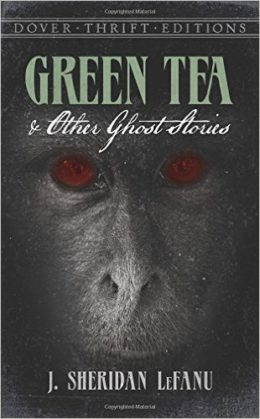

Four years before, he began work on a book about the religious metaphysics of the ancients. He used to fuel this late-night project with copious black tea. Eventually he switched to green tea, which he found better stimulated his thought processes. One night, aboard a dark omnibus home, he saw something strange: two points of luminous red, near the floor. He moved closer and made out a small black monkey grinning at him. He poked it with his umbrella, which passed through the creature’s body without resistance. Spooked, he got off the omnibus early but soon saw the monkey following him. It had to be illusion, a symptom of nervous dyspepsia perhaps.

Yet it persisted, never leaving him, never sleeping, always watching, visible even in total dark via a halo like the red glow of embers. The first year it seemed dazed and languid. It disappeared one night, after a fit of furious agitation, and Jennings prayed he’d never see it again. However, it returned livelier and more malicious. For example, when he was preaching, it would spring on his book so he couldn’t read his text. After another three-month absence, it returned so aggressive it wouldn’t let him pray in private, distracting him whenever he tried, visible even when his eyes were closed. Finally the thing began to speak in his head, blaspheming, ordering him to harm others and himself. Why, he, a man of God, has become a mere abject slave of Satan!

Hesselius calms the clergyman and departs after telling Jennings’s servant to watch his master carefully and summon the doctor at once in any crisis. He spends the night going over the case and planning treatment. Unfortunately, he does this at a quiet inn away from his London lodgings and so doesn’t receive the emergency summons until too late—when he returns to Jennings’s house, the clergyman has cut his own throat.

The doctor concludes with a letter to a professor friend who suffered for a time from similar persecution but was cured (through Hesselius) by God. Poor Jennings’s story was one of “the process of a poison, a poison that excites the reciprocal action of spirit and nerve, and paralyses the tissue that separates those cognate functions of the senses, the external and the interior. Thus we find strange bedfellows, and the mortal and immortal prematurely make acquaintance.”

He goes on to note that Jennings is the only one of fifty-seven such patients he failed to save, due to the man’s precipitant suicide. See his theories about a spiritual fluid that circulates through the nerves. The overuse of some agents, like green tea, can affect its equilibrium and so expose connections between the exterior and interior senses that allow incorporeal spirits to communicate with living men. Alas that Jennings opened his inner eye with his chosen stimulant and then succumbed to his own fears. For, “if the patient do not array himself on the side of the disease, his cure is certain.”

What’s Cyclopean: Jennings’s monkey moves with “irrepressible uneasiness” and “unfathomable malignity.”

The Degenerate Dutch: It’s difficult to interpret Dr. Hesselius’s conviction that green tea in particular is dangerously stimulating to the inner eye. It’s treated as notably more exotic than “ordinary black tea.” Does Hesselius believe everyone in China and Japan wanders around seeing demonic monkeys all the time?

Mythos Making: There are aspects of reality to which most people remain blind and ignorant—and we’re much better off that way. Stripped of its theological component, this essential idea is at the core of much Lovecraft.

Libronomicon: Jennings’s situation is foreshadowed by several Swedenborg quotes about the evil spirits that attend, and try to destroy, humans.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Hesselius diagnoses Jennings posthumously, and somewhat dismissively, with “hereditary suicidal mania.”

Anne’s Commentary

Dubliner Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu gets but passing mention in Supernatural Horror in Literature, even though one of Lovecraft’s “modern masters,” M. R. James, revered the earlier virtuoso of the ghost story. “Green Tea” appears in the collection In a Glass Darkly (1872), along with four other accounts from the archives of Dr. Martin Hesselius, prepared by his literary executor for the curious “laity.” The most famous of “Tea’s” companions is Le Fanu’s masterpiece, Carmilla. Huh. Dr. Hesselius plays so small a part in that novella I forgot he was even involved. But he’s at the center of “Tea.” Just not quite close enough, as we’ll discuss below.

Martin Hesselius, medical metaphysician, is the forerunner of a distinguished line of occult detectives and doctors to the supernaturally harassed. Not long ago we met William Hope Hodgson’s Thomas Carnacki. Before long, I trust, we’ll make the acquaintance of Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence, the Physician Extraordinaire, and Seabury Quinn’s Dr. Jules de Grandin. In more recent times, journalists (Carl Kolchak) and FBI agents (Mulder and Scully) and cute brothers (Dean and Sam Winchester) have led the fight against the uncanny, but surely its most famous warrior can trace his distinguished ancestry back to Hesselius, and that is Dr. Abraham Van Helsing.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula owes much to Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla. Its scholarly hero may be partly based on the vampire expert of that novella, Baron Vordenburg, but Van Helsing more closely resembles the erudite, open-minded and well-traveled Hesselius. In fact, “Van Helsing” is a near-anagram of “Martin Hesselius,” as “Carmilla” was an anagram of the vampire’s true name “Mircalla.” Van Helsing, as Dr. Seward tells us, is also a metaphysician. However well-grounded in the “materialistic” aspects of his profession (like the novel practice of blood transfusion), Van Helsing’s embrace is wide, gathering in the spiritual aspects as well. Both doctors are also pious, and because they believe in a Divine Physician, they can more readily believe in vampires and demons on temporary leave from Hell.

Van Helsing messes up a bit with Lucy Westenra, in the same way Hesselius messes up with Reverend Jennings—both leave unstable patients with inadequately informed guardians, the manservant in Jennings’s case, a crucifix-thieving maid and garlic-removing mother in Lucy’s. All very well to retreat while you formulate a treatment, Dr. Hesselius, but how about leaving a forwarding address to that quiet inn, in case Jennings should flip out in the interim? Oh well. Hesselius saved the other fifty-six patients troubled by an open inner eye and the demons it revealed.

Which is a cool concept, backed here by Swedenborg’s mysticism. Everybody’s got attendant demons. Two at least. And the demons will tend to take whatever animal form best figures forth their essential life and lust. But we aren’t aware of them unless something upsets the balance—equilibrium—of our ethereal nervous fluids. The inner (or third) eye is a much older idea, with analogs in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism, as good Dr. Hesselius no doubt knew. He also places the critical area of the brain “about and above the eyebrow,” like the “brow” chakra or (though more rearward) pineal gland. [RE: Brow chakra, maybe. The pineal gland is above the eyebrow only in the sense that most of the brain can be so described.]

He doesn’t seem to have considered the opening of this eye a fortunate event, as it brought about a “premature” meeting of mortal and immortal, physical and spiritual, entities. In Jennings’s case, the causative agent—the stimulant poison—was green tea. Black tea didn’t bother Jennings, so I guess it was more than caffeine that disordered his nervous fluid. Not that excessive caffeine couldn’t have done a number on him as well, both in the active intoxification stage and during his voluntary withdrawal from his favorite brew. Plus genetics plays a role in the individual’s reaction to caffeine; not surprising then that Hesselius supposes Jennings must have had one parent who was sensitive to supernatural phenomena—who had seen ghosts.

I prefer to think the monkey wasn’t mere stimulant-driven hallucination, though. Because why? Because it’s so splendidly creepy, that’s why. Monkeys are one of those animals that can be so cute until they pull back their lips to expose their killer canines. Their tendency to flash from placid to hyperkinetic is also daunting. Particularly if they’re getting all hyperkinetic at you, bouncing around and grimacing and flailing their little fists, as Jennings’s unwelcome companion does whenever its furlough from Hell is up. There’s also the little matter of the red glowing eyes. Nobody wants to yawn and stretch and glance idly around the midnight study only to see red glowing eyes staring at them. Red glowing eyes are Nature’s way of telling Homo sapiens to get off its duff and run for the cave. Red auras are even worse. And it’s always THERE. Even, in the end, when Jennings closes his eyes. And it starts TALKING. Nope, have to draw the line at talking monkeys, especially when they indulge in blasphemies. I mean, you don’t have to be a Divell-pestered Puritan to object to sacrilegious earworms.

It’s enough to make you call in Dr. Hesselius, and not to be so delayingly coy about it, either.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This is a weird story. The central narrative is compelling, even with the dubious theology. It’s compelling regardless of whether the demonic monkey is real or hallucinatory, an achievement in ambiguity that’s difficult to manage. However, the framing device drains power from the narrative, and the final section in particular is an exercise in patronizing pedanticism that any sensible editor would have cut entirely.

Some of my irritation at the conclusion may stem from a “scientific explanation” that wins some sort of award for Showing Its Age. Maybe in 1872, the idea that green tea opens one’s inner eye to Things Man Was Not Meant to Know seemed… plausible? Vaguely Acceptable Handwavium? Not completely undermined by the contents of most peoples’ kitchen cabinets? Ordinary black tea is entirely harmless, I suppose Properly British. The oxidation process strips Camellia sinensis of its occult powers, don’t you know?

I may be moving from irritation to falling off my bed laughing. It’s been a long week, and I take my amusement where I can get it.

Leaving aside the theological threat to my very soul lurking in my tea canisters, Jennings’s story is deceptively simple in its nightmarishness. If you must have an unpleasant supernatural experience, what could be easier to put up with than an incorporeal monkey? Sure, it’s staring at you all the time, that’s kind of creepy. It stands on your book so you can’t read; my cat does that and is almost as difficult to remove. It distracts you every time you try to complete a thought, and harangues you to destroy yourself and others… honestly, trying to outrun Cthulhu in a steamship is starting to sound pretty good.

Le Fanu’s demonic monkey isn’t too far off from real symptoms of schizophrenia. Voices that don’t seem like oneself, that harass with suggestions of self-harm… difficulty concentrating… hallucinations and unusual religious ideas… the modern psychologist armed with a copy of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual would come to somewhat different conclusions than Hesselius, but would have no difficulty recognizing the details of his report. And they’re frightening details, regardless of whether their ultimate cause is neurological or supernatural. Many people might prefer the supernatural version, where the enemy is at least genuinely external. They’d certainly prefer Hesselius’s version, where a change of diet is enough to effect a real and permanent cure. Assuming you believe his boastful afterword, of course.

Though like many a Lovecraftian narrator, even the patients so cured must suffer a certain disquiet, knowing what still surrounds them even with their “inner eyes” forcibly closed.

Le Fanu had a knack for getting at core creepy ideas this way. From Tea’s depiction of a thinly veiled unseen world full of Things Man Is Better Off Not Knowing and Things Man is Better Off Not Grabbing the Attention Of, we can trace his influence on Lovecraft. The classic “Carmilla,” appearing in the same volume of stories, claims ancestry over the whole genre of modern vampire stories including the better known Dracula. Personally, I think “Green Tea” would have been improved by removing the titular beverage and replacing it with some sort of malign influence from a lesbian vampire. But then, “would be better with a lesbian vampire” just might describe the majority of western literature.

Next week, Matt Ruff’s “Lovecraft Country” provides a travel guide to horrors both mystical and all-too-mundane. It appears as the first of a series of linked stories in his collection of the same name.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.